In a recent rejoinder, Philipp Bagus has followed up on our previous discussion. The present response will focus only on the two most important issues under contention.

The first one is theoretical and refers to the nature of hyperinflations. The second one pertains to counterfactual history. It concerns the question what would have happened to the peso price level in Argentina if Javier Milei, upon rising to power in December 2023, had fulfilled his election promise of shutting down the central bank.

Let us deal with them in turn.

Professor Bagus apparently wishes to use the word “hyperinflation” for any situation in which the price level reaches some critical threshold of strong CPI increases. He argues that hyperinflations could result from strong reductions of the demand for money, just as they have in the past resulted from strong increases of the money stock.

I contend that this is an abuse of language. The consequences of an exploding money stock (at a constant demand for money) are very different from the consequences of an imploding demand for money (at a constant money stock). It is true that in both cases the price level rises, but that is about the only commonality. The processes that go in hand with the rising price level are very different in the two cases.

An imploding demand for money boils down to a rapid shrinking of the old monetary zone. One by one, and often in droves, people are giving up on using the old money. They turn to calculate and exchange in terms of new monies (essentially foreign currencies and precious metals). They pay fantastically high prices in order to get rid of their old money units, once and for all. As the price level rises, the root problem disappears. There is some limited redistribution, essentially in favour of the non-residents who sell foreign currency and precious metals to the residents. There are some bankruptcies, with concomitant losses for the owners of debt securities. But there is no significant devaluation of non-monetary forms of wealth such as real estate and shares; and there is no general and protracted paralysis of the economy. People quickly move on with their lives.

By contrast, when the money stock explodes and the demand for money is coercively stabilised with brutally enforced legal tender laws, then there is no quick and smooth way out. The redistribution of incomes and wealth is massive and may last for many months and even years. Savings evaporate, economic calculation becomes impossible, the division of labour plummets, long-term planning and investment are out of the question. The value of all fixed-income debt securities is wiped out. Sooner or later people start selling real estate, shares of corporations, paintings, and other valuables at discount prices, just to make it through the week or the day. Only at the very end of this process, when overpowering economic pain drives the despairing populace to disobeying their government, only then the demand for money plummets and brings about the healing process that we have described above.

Calling these two very different processes by the same name cannot fail to spread confusion. Some twenty years back, Peter Bernholz has catalogued all previous hyperinflations (see his book Monetary Regimes and Inflation). There was not one single case in which hyperinflations occurred at a constant (or slowly changing) money stock. In all cases, the money stock had been massively increased in order to fund enormous public deficits. And when we look at the subsequent hyperinflations that occurred after his book came into print, we find that things have not changed.

In other words, not only are there fundamental praxeological differences between the various processes that may lead to a rising price level, but in practice the only process that has ever produced a hyperinflation is the one that results from an exploding money stock. This has been called hyperinflation. Using this word in a different sense comes with the risk of spreading confusion and unwarranted fears.

Let me now turn to the second issue. What would have happened to the peso price level if president Milei had shut down the central bank in early 2024?

The standard response from next to any economist worth his salt is that it would have imploded under the weight of a rapidly shrinking money stock. At least that is what I thought (and still think) to be the standard response. We may imagine different scenarios of shutting down the central bank. Most of them would entail a staggering reduction of the base-money stock. For the sake of argument, we may assume that the base-money stock remains henceforth frozen. But even then, the overall money stock would shrink because the quantity of fiduciary media produced by the commercial banks would plummet. Many of them would go bankrupt without central bank assistance, and the survivors would have to massively prop up their prudential reserves.

It is true that at the end of 2023, the demand for pesos was falling. But again, I would expect few economists to see here the primary driver of the price-inflation of those years. I think most of us would look at monetary aggregates first and expect the demand for pesos to adjust to the vagaries of monetary policy. Things may be different in the later stages of a hyperinflation, as we have discussed before, but Argentina was not in such a late stage at the end of 2023.

But then comes Philipp Bagus and tells us that Argentina was in an advanced stage (though not the very last stage) of a burgeoning hyperinflation and the demand for pesos was plummeting. In this context, he asserts, shutting down the central bank would have destroyed any confidence in the peso. It therefore would have entailed increased price-inflation and not any sort of price-deflation:

The preceding government had increased the money supply enormously, accelerating price inflation. An inflationary spiral had been set off in which a lower demand for pesos leads to higher prices (most visibly reflected in the dollar exchange rate), leading to further reductions in confidence and in the demand for pesos, and so on. It is not necessary that the money supply continues to increase until the very last stage of hyperinflation; the preceding expansion may already have set off the loss of confidence. The elimination of the central bank on Milei’s first day in office would not have stopped the process of loss of confidence; rather, the peso would have lost the hope of being convertible at a fixed rate into dollars.

This story prompted my initial reaction and has animated our subsequent discussion. I found it (and still find it) completely implausible. Above, I have dealt with some of the theoretical and terminological questions that here come into play. But there is also the question of the empirical accuracy of Professor Bagus’ story. And I don’t have the impression that he has got his facts right.

It stretches my imagination that Argentinians would have “lost their confidence” in the peso if the latter could no longer be expected to be convertible into dollars at a fixed rate. For the past twenty years, and probably even longer, there was not any significant period of exchange-rate stability. The peso was on a permanent downhill trajectory. How could there be any hope for convertibility at a fixed rate?

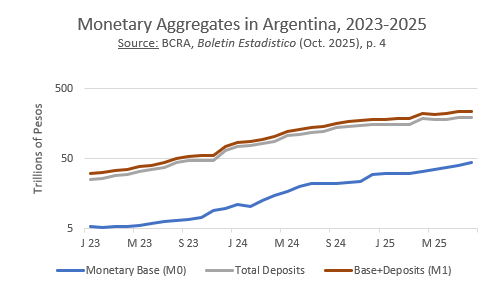

Furthermore, it not true that the previous government had increased the money supply “enormously” – if we understand this to be “much more than previous governments” or “much more than the Milei administration”. It certainly did not double, triple, or quadruple the money stock, as it is often the case in true hyperinflations. The actual evolution of the Argentinian M0 and M1 money aggregates (I could not find the data necessary to calculate M2) from January 2023 through August 2025 looks like this:

Notice the logarithmic scale. The growth of the money stock was not significantly higher under the previous government, except for the very last month of its administration. Under president Milei, the inflation of the money stock proceeded more or less as before. The central bank and the commercial banks enabled his government, in the memorable words of Yanis Varoufakis, to “borrow zillions of dollars”. And even though the debt-to-GDP ratio has decreased significantly in this inflationary process, the fact remains that trillions of pesos and billions of dollars have been redistributed, as under his predecessor, from the bottom to the top end of the economic food chain.

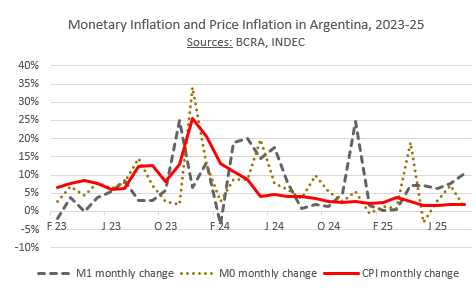

Even if we look at the price-inflation index and contrast it with the monthly growth rates of M0 and M1, we do not find any evidence of a situation resembling advanced stages of a hyperinflation. We do not find any hyperinflation-level difference between the Milei period and his predecessor. There was a notable “galloping” spike in November and December 2023, but nothing even close to what is commonly called a hyperinflation. And, most importantly, this galloping price-inflation can readily be explained as a consequence of previous monetary inflation. When M1 growth started to collapse from November through February, at some point even reducing the M1 aggregate, the price level movements quickly followed the same tendency. There is nothing miraculous about this. There is no need to bring in any extraordinary hypothesis about a sudden hyperinflation-style reduction of the demand for money.

In the light of these facts, I think it was unwarranted to resort to the rather specious assumption that the demand for money had somehow become the primary driver of price-inflation at the end of 2023, because Argentinians had suddenly “lost their confidence” in the peso. There was no need to deviate from the typical explanation of such situations and to ascribe a special role to the demand for money in that context. It was erroneous to think that shutting down the central bank would exacerbate price-inflation or even entail a hyperinflation.